01.05.2005 | Peter Maass | The New York Times

In a country of tough guys, Adnan Thabit may be the toughest of all. He was both a general and a death-row prisoner under Saddam Hussein. He favors leather jackets no matter the weather, his left index finger extends only to the knuckle (the rest was sliced off in combat) and he responds to requests from supplicants with grunts that mean »yes » or »no. » Occasionally, a humble aide approaches to spray perfume on his hands, which he wipes over his rugged face.

General Adnan, as he is known, is the leader of Iraq’s most fearsome counterinsurgency force. It is called the Special Police Commandos and consists of about 5,000 troops. They have fought the insurgents in Mosul, Ramadi, Baghdad and Samarra. It was in Samarra, 60 miles north of Baghdad in the heart of the Sunni Triangle, where, in early March, I spent a week with Adnan, himself a Sunni, and two battalions of his commandos. Samarra is Adnan’s hometown, and he had come to retake it. As the offensive to drive out the insurgents got under way, the only area securely under Adnan’s control was a barricaded enclave around the town hall, where he grimly presided over matters of war and peace, but mostly war, chain-smoking Royal cigarettes at a raised desk in the mayor’s office. With a jowly face set in a permanent scowl, Adnan is perfectly suited to the grim realities of Iraq, and he knows it. When an admiring American colonel compared him to Marlon Brando in »The Godfather, » Adnan took it as a compliment and smiled.

Early one evening, I was sitting in his office when an officer entered with a click of his heels — an Iraqi salute of sorts. He reported to Adnan that a rebel weapons cache had been discovered, and Adnan congratulated him — but issued a warning. »If even one AK-47 is stolen, » he said, »I will kill you. » After a pause, he smiled and refined the threat. »No, » he said, »I will kill your » — and he used a coarse word that referred to the officer’s most private body part. There was nervous laughter. Everyone seemed certain that not a single gun, or single anything, would go missing.

Not long ago, hard men like Adnan, especially Sunnis, were giving orders to no one. Six weeks after the fall of Baghdad, the Coalition Provisional Authority dismissed the Sunni-led Iraqi Army, and the United States military set out to rebuild Iraq’s armed forces from the ground up, training new officers and soldiers rather than calling on those who knew how to fight but had done so in the service of Saddam Hussein. By late last year, though, it had become clear that the new American-trained forces were not shaping up as an effective fighting force, and the old guard was called upon. Now people like Adnan, a former Baathist, have been given the task of defeating the insurgency. The new strategy is showing signs of success, but it is a success that may carry its own costs.

A couple of hours after Adnan issued his AK-47 threat, I sat with him watching TV. This was business, not pleasure. The program we were watching was Adnan’s brainchild, and in just a few months it had proved to be one of the most effective psychological operations of the war. It is reality TV of sorts, a show called »Terrorism in the Grip of Justice. » It features detainees confessing to various crimes. The show was first broadcast earlier this year and has quickly become a nationwide hit. It is on every day in prime time on Al Iraqiya, the American-financed national TV station, and when it is on, people across the country can be found gathered around their television sets.

Those being interrogated on the program do not look fearsome; these are not the faces to be found in the propaganda videos that turn up on Web sites or on Al Jazeera. The insurgents, or suspected insurgents, on »Terrorism in the Grip of Justice » come off as cowardly lowlifes who kill for money rather than patriotism or Allah. They tremble on camera, stumble over their words and look at the ground as they confess to everything from contract murders to sodomy. The program’s clear message is that there is now a force more powerful than the insurgency: the Iraqi government, and in particular the commandos, whose regimental flag, which shows a lion’s head on a camouflage background, is frequently displayed on a banner behind the captives.

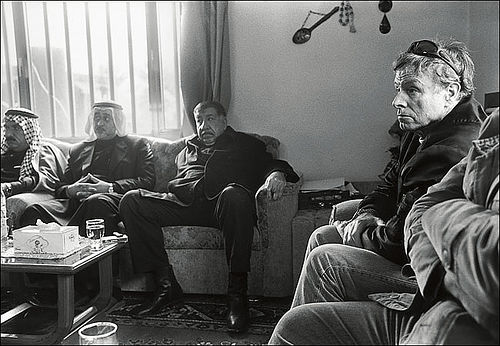

Before the show began that evening, Adnan’s office was a hive of conversation, phone calls and tea-drinking. Along with a dozen commandos, there were several American advisers in the room, including James Steele, one of the United States military’s top experts on counterinsurgency. Steele honed his tactics leading a Special Forces mission in El Salvador during that country’s brutal civil war in the 1980’s. Steele’s presence was a sign not only of the commandos’ crucial role in the American counterinsurgency strategy but also of his close relationship with Adnan. Steele admired the general. »He’s obviously a natural type of commander, » Steele told me. »He commands respect. »

Things quieted in the office once the episode of »Terrorism in the Grip of Justice » began. First, a detainee admitted to having homosexual relations in a mosque. Then several other suspected insurgents made their confessions; two of them had been captured by Adnan’s commandos in Samarra, and their confessions were taped, just hours before, in this very office. Adnan sat smoking Royals and watching the show like a proud producer.

»It has a good effect on civilians, » he had told me, through an interpreter. »Most civilians don’t know who conducts the terrorist activities. Now they can see the quality of the insurgents. » Earlier he said: »Civilians must know that these people who call themselves resisters are thieves and looters. They are dirty. In every person there is good and bad, but in these people there is only bad. »

The episodes of the program I have seen depict an insurgency composed almost entirely of criminals and religious fanatics. The insurgency as understood by American intelligence officers, is a more complex web of interests and fighters. Most of the insurgency is composed of Sunnis, and it is generally believed that Baathists hold key positions. But the commandos, who are the stars of »Terrorism in the Grip of Justice, » are also led by Sunnis and have many former Baathists in their ranks, so the Sunni and Baathist aspect of the insurgency is carefully obscured.

Of course, propaganda need not be wholly accurate to be effective. The real problem with the program, according to its most vocal critics — representatives of human rights groups — is that it violates the Geneva Conventions. The detainees shown on »Terrorism in the Grip of Justice » have not been charged before judicial authorities, and they appear to be confessing under duress. Some detainees are cut and bruised. In one show, a former policeman with two black eyes confessed to killing two police officers in Samarra; a few days after the broadcast, the former policeman’s family told reporters, his corpse was delivered to them. The government’s human rights minister has initiated an investigation.

»Terrorism in the Grip of Justice » is a ratings success because it humiliates the insurgency, satisfying a popular desire for vengeance against the men who spread terror and death. Yet the program plyas rough not only with its confessing captives but also with the rules and laws that govern the conduct of war. As I learned in Samarra, this approach was not just for television. It was Adnan’s effective yet brutal way of conducting a counterinsurgency.

Building a Home-Grown Counterinsurgency

Most of the Pentagon’s official statements in the past two years about the ability of Iraqis to police their own country have been exaggerated. But now reality is beginning to catch up with rhetoric. In the months that followed the January elections in Iraq, attacks on allied forces reportedly fell to 30 to 40 a day in February and March, from 140 just before the vote. It’s hard to tell whether this trend will continue; in late April the insurgency showed signs of renewed strength. But the successes that the counterinsurgency has enjoyed are in no small part because of Adnan’s commandos. With American forces in an advisory role, the commandos, as well as a few other well-led units, like the Iraqi Army’s 36th Commando Battalion and its 40th Brigade in Baghdad, inflicted more violence upon insurgents than insurgents inflicted upon them. That is much of what fighting an insurgency amounts to. But successful counterinsurgencies, if history is a guide, tend not to be pretty, especially in countries where violence has been a way of life and rules governing warfare and human rights have been routinely ignored by those in uniform.

The template for Iraq today is not Vietnam, to which it has often been compared, but El Salvador, where a right-wing government backed by the United States fought a leftist insurgency in a 12-year war beginning in 1980. The cost was high — more than 70,000 people were killed, most of them civilians, in a country with a population of just six million. Most of the killing and torturing was done by the army and the right-wing death squads affiliated with it. According to an Amnesty International report in 2001, violations committed by the army and its associated paramilitaries included »extrajudicial executions, other unlawful killings, ‘disappearances’ and torture. . . . Whole villages were targeted by the armed forces and their inhabitants massacred. » As part of President Reagan’s policy of supporting anti-Communist forces, hundreds of millions of dollars in United States aid was funneled to the Salvadoran Army, and a team of 55 Special Forces advisers, led for several years by Jim Steele, trained front-line battalions that were accused of significant human rights abuses.

There are far more Americans in Iraq today — some 140,000 troops in all — than there were in El Salvador, but U.S. soldiers and officers are increasingly moving to a Salvador-style advisory role. In the process, they are backing up local forces that, like the military in El Salvador, do not shy away from violence. It is no coincidence that this new strategy is most visible in a paramilitary unit that has Steele as its main adviser; having been a key participant in the Salvador conflict, Steele knows how to organize a counterinsurgency campaign that is led by local forces. He is not the only American in Iraq with such experience: the senior U.S. adviser in the Ministry of Interior, which has operational control over the commandos, is Steve Casteel, a former top official in the Drug Enforcement Administration who spent much of his professional life immersed in the drug wars of Latin America. Casteel worked alongside local forces in Peru, Bolivia and Colombia, where he was involved in the hunt for Pablo Escobar, the head of the Medellin cocaine cartel.

Both Steele and Casteel were adamant in discussions with me that they oppose human rights abuses. They stressed that torture and death-squad activity are counterproductive. Yet excesses of that sort were endemic in Latin America and in virtually every modern counterinsurgency. American abuses at Abu Ghraib and other detention centers in Iraq and Afghanistan show that first-world armies are not immune to the seductions of torture.

Until last year, the United States military tried to defeat the insurgency on its own, with Iraqi forces playing only a token role. The effort did not succeed. For every Iraqi detained by G.I.’s, 10 more seemed to join the insurgency, thanks to questionable American tactics: shooting at the whiff of a threat, yelling at civilians, detaining Iraqis indiscriminately, placing hoods over the heads of detainees. With insurgent attacks becoming more frequent and also more gruesome in the spring of 2004, American generals realized that they needed to create, or find, effective Iraqi forces.

Last June, Lt. Gen. David Petraeus, who commanded the 101st Airborne during the invasion, returned to Iraq to take charge of the sputtering training effort. He arrived in the wake of a major embarrassment — when the first U.S.-trained battalion of Iraqi troops was ordered to Falluja to support an offensive by the Marines, many of them deserted or refused to fight. General Petraeus was given the resources and clout to turn things around, but in the months that followed things did not appear to be improving. When insurgents attacked the northern city of Mosul in the fall, the U.S.-trained police force there collapsed, abandoning its stations. Across the country, police officers were being killed by the dozens in mortar and car-bomb attacks; demoralized and outgunned, they retreated to fortified stations or simply stayed home.

A scathing report from the Center for Strategic and International Studies, still in draft form but posted on the center’s Web site, blames senior American officials for these failures of Iraqi will. »The police and the bulk of the security forces were given grossly inadequate training, equipment, facilities, transport and protection, » states the report, written by Anthony Cordesman, a military expert and former Pentagon official. »These problems were then compounded by recruiting U.S. police advisers — some more for U.S. domestic political reasons than out of any competence for the job — with no area expertise and little or no real knowledge of the mission that the Iraqi security and police forces actually had to perform. » The report seems to be referring to, among others, Bernard Kerik, the former New York City police commissioner, who was the first police adviser to L Paul Bremer III, administrator of the Coalition Provisional Authority. Kerik left after three and a half months. Although the report notes some progress in recent months, it concludes: »Unprepared Iraqis were sent out to die. . . . The fact that some died as a result of U.S. incompetence and neglect was the equivalent of bureaucratic murder. »

A key problem early on was that United States officials focused on the number of recruits rather than on their quality. Not only was the wrong metric being used to measure progress; the metric was being manipulated. Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice, at her confirmation hearing in January, stated that 120,000 Iraqis were trained and equipped. Senator Joseph Biden countered that no more than 14,000 of them were reliable fighters. Biden had a point: many of the Iraqis in Rice’s head count barely knew how to fire a weapon. A recent report from the Government Accountability Office said the Pentagon’s tallies have included tens of thousands of police officers who did not even report for duty. »If you are reporting AWOL’s in your numbers, I think there’s some inaccuracy in your reporting, » Joseph Christoff, the G.A.O. official who presented the report to Congress, commented to The Los Angeles Times.

Last summer, with the security situation deteriorating, some Iraqi and American officials began to argue that the time had passed for a »clean hands » policy that rejected most of the experienced people who had fought for Saddam Hussein. The first official to take action was Falah al-Naqib, interior minister under the interim government of Ayad Allawi. In September, Naqib formed his own regiment, the Special Police Commandos, drawn from veterans of Hussein’s special forces and the Republican Guard. As its leader, he chose General Adnan, not only because Adnan had a useful collection of colleagues from Iraq’s military and security networks, but also because Adnan is Naqib’s uncle.

Naqib did not ask for permission or training or even equipment from the United States military; he formed and armed the commandos because the U.S. military would not. »One of the biggest mistakes made by the coalition forces is that they started from zero, » he told me in his office in the Green Zone in Baghdad. »Our army and police are 80 years old. They have lots of experience. They know more about the country and the people, and about the way the insurgents are fighting, than any foreign forces. »

Initially, Petraeus wasn’t even told of the commandos; Iraqis and American civilians at the Ministry of Interior had lost faith in the U.S. military. The American who was most involved in the commandos’ creation was Casteel, Naqib’s senior American adviser. Casteel, who previously worked for Paul Bremer in the Coalition Provisional Authority, realized that the de-Baathification policy had to be altered and that Naqib was the person to do it. »He was not looking for top Baathists or people with blood on their hands, » Casteel said. »But a tremendous amount of people who worked in the government or army weren’t either of those. So why start from scratch when we can start in the middle? That’s where the commando idea was formed. »

After the commandos set up their headquarters at a bombed-out army base at the edge of the Green Zone, Petraeus went for a visit. He was pleasantly surprised, he told me, to see a force that was relatively disciplined and well motivated. He knew the commandos were officers and soldiers who had served Saddam Hussein, he knew many of them were Sunni and he certainly knew they were not under American control. But he also sensed that they could fight. He challenged some of them to a push-up contest. He was not just embracing a new military formation; he was embracing a new strategy. The hard men of the past would help shape the country’s future.

Petraeus decided that the commandos would receive whatever arms, ammunition and supplies they required. He also assigned Steele to work with them. In addition to his experience in El Salvador, Steele had been in charge of retraining Panama’s security forces following the ousting of President Manuel Noriega. When I asked him to describe Adnan’s leadership qualities, Steele drew on the vocabulary he learned in Latin America. Adnan, he said approvingly, was a caudillo — a military strongman.

Doing It the Iraqi Way

Adnan’s offensive turned Samarra into a proving ground for this new strategy, the most comprehensive effort to date in which United States-backed Iraqi forces sought to retake an insurgent city. Code-named City Market, the offensive has involved weeks of raids by commandos and their American advisers. After the first wave of raids, a new corps of police officers and Interior Ministry troops known as Public Order Battalions were deployed to take command of the streets.

Samarra has a population of a quarter million, though many have fled after two years of warfare. The population is divided among seven tribes whose rivalries created fertile soil for the insurgency to take root. Since 2003, the city has often been under the control of the insurgents. In October, the United States launched an offensive to retake the city, but the moment the Bradleys and Humvees departed, the insurgents returned. (Voter turnout in the election in January was less than 5 percent.)

When I arrived in March, the part of Samarra under American and commando control — the City Hall and a Green Zone around it — was a small parcel of land ringed with a phalanx of concrete barriers, barbed wire and shoot-to-kill lookouts. The main roads into the city were blocked by checkpoints at which Iraqi soldiers searched every vehicle. American and Iraqi forces rarely left the Green Zone on foot, conducting their patrols in heavily armed convoys, and the Green Zone was hit by mortars almost every day.

There were just a few hundred G.I.’s in Samarra, living in the Green Zone on two bases, Razor and Olsen. The conditions were spartan; soldiers were housed in cramped rooms, they used portable toilets as latrines and hot dinners were served just three nights a week. At Olsen, a former casino that is home to troops of the Wisconsin Army National Guard and the Third Infantry Division, the soldiers I met spent most of their off-hours lifting weights, e-mailing loved ones back home or playing Halo on Xboxes, unwinding from real combat by engaging in simulated combat. Three teams of a dozen or so G.I.’s went out on the raids with the Iraqi commandos. (The other soldiers in the city performed logistical, administrative and perimeter-security duties.) One team was composed of Special Forces soldiers, another was drawn from the Wisconsin National Guard and the third, with which I spent most of my time on patrol, was staffed by soldiers of the Third Infantry Division. The squad leader was Capt. Jeff Bennett, a 26-year-old whose father is in the Air Force.

Captain Bennett was on his second tour in Iraq. During the invasion, he was among the Third Infantry Division troops who captured Baghdad airport against stiff resistance from Republican Guard forces. Bennett wears his division patch on the shoulder of his uniform, and soon after he arrived in Samarra, the patch was recognized by a few of the Iraqi commandos, who informed him that they had been in the Republican Guard unit at the airport that fought his unit. Initially, Bennett was leery about going into combat with men he had tried to kill, and who had tried to kill him, but after their first battle together, fighting shoulder to shoulder against insurgents, his doubts disappeared.

»That’s the great equalizer, » Bennett said. »You get into a firefight with someone, they come to your side, return fire, cover another person. That kind of seals the relationship. »

Many of the commando raids occurred at night. One evening, I watched as preparations began on the street outside City Hall. A group of about 50 Iraqis strapped on their body armor, inserted bullet clips into their AK-47’s and listened to heavy metal on the stereos of their American-supplied Dodge pickups, which now bore coats of camouflage paint and machine guns on their flatbeds. The commandos talked and joked loudly, exuding an alpha-male confidence. Bennett’s squad mixed easily with the commandos, exchanging greetings in the Arabic phrases they learned.

The commandos cultivate a vaguely menacing look. They wear camouflage uniforms, but also irregular clothing, like black leather gloves and balaclavas — not to hide their identities but to inspire fear among the enemy. It is a look I saw among the Serbian paramilitaries who terrorized Croatia and Bosnia during the Balkan wars in the 90’s, and it is the look of the paramilitaries that operated in Latin America a decade earlier.

When it was time to go, the commandos moved out in their Dodges, and Bennett’s team followed in three armored Humvees. Bennett was not sure of the precise destination that evening; though the Iraqis and Americans had swapped lists of high-value targets, the commandos generally decided which ones would be pursued. The patrol moved out with lights off, slipping through Samarra’s barren streets; there was a curfew in effect, and even the city’s many stray dogs seemed to have taken shelter. The patrol eventually pulled to a halt at a house a few miles from the Green Zone. A man there, apparently willing to cooperate, said he knew where a number of insurgents could be found, and he led the way to a nearby house. Those inside were brought out, one by one. The man identified one as an insurgent, and he was flex-cuffed, blindfolded and thrown into the back of a truck.

The convoy moved on and made many more stops. House after house was searched. Sometimes the commandos broke down doors or shot off locks. Other times they entered with a polite knock and had friendly discussions, departing with handshakes and smiles. The commandos are far more skilled than American troops I’ve spent time with at knowing, intuitively, whether someone represents a threat. A few men were detained as the evening unfolded, and when they offered resistance or didn’t provide information as quickly as the commandos desired, they were punished with a quick kick, slap or punch.

A little after 2 a.m., the commandos rolled into a neighborhood where the homes were surrounded by walls and had satellite dishes on their roofs. A man who was detained earlier in the night pointed the commandos toward one house. They entered and soon emerged with a confiscated computer, but whomever they hoped to find inside was not there.

The officer in charge of the raid — a Major Falah — now made it clear that he believed the detainee had led them on a wild-goose chase. The detainee was sitting at the side of a commando truck; I was 10 feet away, beside Bennett and four G.I.’s. One of Falah’s captains began beating the detainee. Instead of a quick hit or slap, we now saw and heard a sustained series of blows. We heard the sound of the captain’s fists and boots on the detainee’s body, and we heard the detainee’s pained grunts as he received his punishment without resistance. It was a dockyard mugging. Bennett turned his back to face away from the violence, joining his soldiers in staring uncomfortably at the ground in silence. The blows continued for a minute or so.

Bennett had seen the likes of this before, and he had worked out his own guidelines for dealing with such situations. »If I think they’re going to shoot somebody or cut his finger off or do any sort of permanent damage, I will immediately stop them, » he explained. »As Americans, we will not let that happen. In terms of kicking a guy, they do that all the time, punches and stuff like that. » It was a tactical decision, Bennett explained: »You only get so many interventions, and I’ve got to save my butting in for when there is a danger it could go over the line. » But even when he doesn’t say anything, he explained, »they can tell we’re not enjoying it. We’re just kind of like, ‘O.K., here we go again. »’

Though the commandos and their American advisers were working together in Samarra, their approaches were decidedly different. The American way of combat is heavily planned, with satellite maps, G.P.S. coordinates and reconnaissance drones. The Iraqi way is improvisational, relying less on honed skills and high-tech than gut instinct and (literally) bare knuckles. It is the Americans who are learning to adapt. At the bottom of printed briefings that American soldiers receive at the bases in Samarra, a quotation from T.E. Lawrence is appended: »Better the Arabs do it tolerably than that you do it perfectly. It is their war, and you are to help them, not to win it for them. »

Threatening to Kill a Suspect’s Son

On March 8, I went on a series of raids with the commandos, traveling in a Humvee with Maj. Robert Rooker, an artillery officer based in Tikrit who was dispatched to Samarra to serve as my escort. The leader of the American squad was Andrew Johansen, a 30-year-old lieutenant in the Wisconsin Army National Guard. The commandos led the way in a half-dozen Dodges, with Johansen’s team following in three Humvees. The target was a house outside Samarra where Najim al-Takhi, thought to be the leader of an insurgent cell, was believed to be hiding.

The commandos reached an isolated farmhouse and detained al-Takhi’s son, who looked to be in his early 20’s. This was an excellent catch. The son of a suspect usually knows where the suspect is hiding; if not, he can be detained and used as a bargaining chip to persuade the father to surrender. With al-Takhi’s son flex-cuffed in the back of one of the pickups, the commandos, excited, drove to another farmhouse less than a mile away. They believed that al-Takhi might be there, but a quick search yielded nothing. The leader of this raid was a short, chubby captain who was enthusiastic and, as I noticed on previous raids, effective at leading his men. (When I later asked his name, he refused to give it.) The captain was convinced that al-Takhi was nearby, but the son was telling him he didn’t know where his father was. Was he lying?

The captain’s methods were swift and extreme. He yelled at the son, who was wearing a loose tunic; in the tussle of the arrest the young man had lost one of his sandals. The captain pushed him against a mud wall and told everyone else to move away. Standing less than 10 feet from the young man, the captain aimed his AK-47 at him and clicked off the safety latch. He was threatening to kill him. I was close enough to catch some of the dialogue on my digital recorder.

»Where is your father? » the captain shouted. »Say where your father is! »

»He left early in the morning, » the son responded, clearly in terror. »I told my father to divorce my mother, to not leave us in such a state. »

The son asked for mercy. »I swear, if I knew where he is, I would for sure take you to him. » He looked around. »Oh, God, what should I do? »

The captain was not persuaded.

»Just tell us where he is, and we will release you now, » he shouted.

»I swear to you, though you did not ask me to make an oath, instead of enduring all these beatings I would tell you where he is if I knew. »

Major Rooker was just a few feet from the angry captain. He moved closer and nudged the captain’s AK-47 toward the ground.

»You are a professional soldier, » Rooker told him. »You know and I know that you need to put the weapon down. »

The captain scowled but ended the execution drama.

»O.K., guys, » he shouted to his men, »let’s ride back. »

As the commandos pulled their prisoner away, Lieutenant Johansen conferred with Rooker. »They don’t operate the way we do, that’s for damn sure, » Johansen said. »We have to be nice to people. » Especially in the aftermath of Abu Ghraib, they both knew that threatening a prisoner with death, they both knew, was illegal under the Geneva Conventions.

»I think it was all an act to try and get him to talk, » Rooker said. »But for a fraction of a second I didn’t know that. I thought the guy was going to cap him. »

The commandos moved about 100 yards away, where they interrogated the young man again, this time without an AK-47 in his face. With an execution no longer in the offing, Rooker decided to not further irritate the captain. »They’ll shake him down a little bit more, » he said to the driver of his Humvee. »Stay back and let them do their job. »

Later, I asked Johansen about what had happened.

»I’m about 99 percent sure it was intimidation to put fear into the guy, » he told me. »I know they use different means of interrogation, but I didn’t expect them to raise a weapon at a detainee. I don’t think they know the value of human life Americans have. If they shoot somebody, I don’t think they would have remorse, even if they killed someone who was innocent. »

Inside the Detention Center

In Samarra, the commandos established a detention center at the public library, a hundred yards down the road from the City Hall. The library is a one-story rose-hued building surrounded by a five-foot wall. There is a Koranic inscription over its entrance: »In the name of Allah the most gracious and merciful, Oh, Lord, please fill me with knowledge. »

These days, the knowledge sought under its roof comes not from hardback books but from blindfolded detainees. In guerrilla wars of recent decades, detention centers have played a notorious role. From Latin America to the Balkans and the Middle East, the worst abuse has taken place away from the eyes of bystanders or journalists. During my first few days in the city, I was told I could not visit the center; I was able only to observe, discreetly, as detainees were led into it at all hours. But one day Jim Steele asked whether I wanted to interview a Saudi youth who had been captured the previous day. I agreed, and he took me to the detention center.

We walked through the entrance gates of the center and stood, briefly, outside the main hall. Looking through the doors, I saw about 100 detainees squatting on the floor, hands bound behind their backs; most were blindfolded. To my right, outside the doors, a leather-jacketed security official was slapping and kicking a detainee who was sitting on the ground. We went to a room adjacent to the main hall, and as we walked in, a detainee was led out with fresh blood around his nose. The room had enough space for a couple of desks and chairs; one desk had bloodstains running down its side. The 20-year-old Saudi was led into the room and sat a few feet from me. He said he had been treated well and that a bandage on his head was a result of an injury he suffered in a car accident as he was being chased by Iraqi soldiers.

A few minutes after the interview started, a man began screaming in the main hall, drowning out the Saudi’s voice. »Allah! » he shouted. »Allah! Allah! » It was not an ecstatic cry; it was chilling, like the screams of a madman, or of someone being driven mad. »Allah! » he yelled again and again. The shouts were too loud to ignore. Steele left the room to find out what was happening. When returned, the shouts had ceased. But soon, through the window behind me, I could hear the sounds of someone vomiting, coming from an area where other detainees were being held, at the side of the building.

Earlier, I spoke briefly with an American counterintelligence soldier who works at the detention center. The soldier, who goes by the name Ken — counterintelligence soldiers often use false names for security reasons — said that he or another American soldier was present at 90 percent of the interrogations by the commandos and that he had seen no abuse. I didn’t have an opportunity to ask him detailed questions, and I wondered, in light of the beatings that I had seen soldiers watch without intervening, what might constitute abuse during interrogation. I also wondered what might be happening when American intelligence soldiers weren’t present.

The Saudi I interviewed seemed relieved to have been captured, because his service in the insurgency, he said, was a time of unhappy disillusion. He came to Iraq to die with Islamic heroes, he said, but instead was drafted into a cell composed of riffraff who stole cars and kidnapped for money and attacked American targets only occasionally. When I asked, through an interpreter, whether he had planned to be a suicide bomber, he looked aghast and said he would not do that because innocent civilians would be killed; he was willing to enter paradise by being shot but not by blowing himself up. He gladly gave me the names of the members of the cell. One was a Syrian who had been arrested with him.

That evening, as I was eating dinner in the mess hall at Olsen base, I overheard a G.I. saying that he had seen the Syrian at the detention center, hanging from the ceiling by his arms and legs like an animal being hauled back from a hunt. When I struck up a conversation with the soldier, he refused to say anything more. Later, I spoke with an Iraqi interpreter who works for the U.S. military and has access to the detention center; when I asked whether the Syrian, like the Saudi, was cooperating, the interpreter smiled and said, »Not yet, but he will. »

One afternoon as I was standing near City Hall, I heard a gunshot from within or behind the detention center. In previous days, I saw or heard, on several occasions, accidental shots by commandos — their weapons discipline was far from perfect — so I assumed it was another negligent discharge. But within a minute or so, there was another shot from the same place — inside or behind the detention center.

It was impossible to determine what was happening at the detention center, but there was certainly cause to worry. A State Department report released last month noted that Iraqi authorities have been accused of »arbitrary deprivation of life, torture, impunity, poor prison conditions — particularly in pretrial detention facilities — and arbitrary arrest and detention. » A report by Human Rights Watch in January went further, claiming that »unlawful arrest, long-term incommunicado detention, torture and other ill treatment of detainees (including children) by Iraqi authorities have become routine and commonplace. »

When I returned to the United States, I asked the American authorities in Samarra for a comment about potential human rights abuses at the detention center. They forwarded my e-mail message to a spokesperson for the Iraqi Interior Ministry, who wrote in reply: »The Ministry of Interior does not allow any human rights abuses of prisoners that are in the hands of Ministry of Interior Security Forces. . . . Reports of human rights violations are deeply investigated by the Ministry of Interior’s Human Rights Department. »

The Uses of Fear

In El Salvador, a subpar army fought an insurgency to a standoff that eventually led to a political solution. Kalev Sepp, who was a Special Forces adviser in El Salvador and is currently a professor at the Navy’s Center on Terrorism and Irregular Warfare, said he believes that the handful of United States-trained Salvadoran strike battalions made the difference. »Those six battalions held back the guerrillas for years, » he said in a recent phone interview. »The rest of the army was guarding bridges and power lines. »

In Iraq, the insurgency does not fight everywhere; most attacks occur around Baghdad and in the Sunni Triangle. This allows a small and agile counterinsurgency force to play a disproportionately large role, and the commandos are precisely that kind of force. As a paramilitary unit, they are not slowed down by heavy weapons, and they do not engage in the attrition warfare of lumbering army regiments with thousands of troops and tanks and artillery pieces. Instead, they go wherever there is trouble, racing up and down the highways at 90 miles an hour in their Dodge trucks (so quickly, in fact, that Humvees cannot keep up with them). When Mosul erupted in November, with local police officers fleeing their stations as insurgents took control of the streets, several battalions of commandos sped to the city and restored order (or what passes for order in Iraq). When National Guard troops collapsed in Ramadi earlier this year, a battalion of commandos was rushed in. The commandos in Samarra will return to their base in Baghdad once their mission is completed — or they will head to the next hot spot.

Intriguingly, a reputation for severity can accomplish as much as severity itself. One day a troublesome local leader, Sheik Taha, arrived for a meeting with Adnan at Samarra’s Town Hall. Lt. Col. Mark Wald, who commands the Third Infantry Brigade in the city, told me that Taha supported the insurgency but was reconsidering his options now that Adnan had arrived with his commandos. I assumed that Adnan conveyed a message to the sheik that was not dissimilar to his warning to the commando who found an arms cache — do as I say or you will lose a precious body part.

After the meeting, I asked Adnan whether the sheik had agreed to fall in line.

»It is not important whether he is with us or against us, » he growled in response. »We are the authority. We are the government, and everybody must cooperate with us. He is beginning to cooperate with us. »

Adnan’s remarks were put into context for me by Wald, a graduate of the University of California at Berkeley. He pointed at the door behind which Adnan and Taha met. »This is what I consider an Iraqi solution, » he said. »The beauty of an Iraqi solution is that they know how justice has been dealt with in the past years. They know what they are subject to. We are bound by laws. I think they are, too, but that doesn’t mean a guy like Sheik Taha doesn’t go in there fearing it’s an eye for an eye, tooth for a tooth. »

No End in Sight

Paramilitary forces have a tendency to become politicized. Whereas the mission of army troops is national — they exist to defend against foreign threats — paramilitaries are used for internal combat. In the Middle East and elsewhere, they often serve the interests of the regime or of whatever faction in the regime controls them. (It is no accident that the commandos are run out of the Interior Ministry and not the Defense Ministry.) In a country as riven as Iraq — with Shiites, Sunnis, Kurds and Turkmen vying for power — a paramilitary force that is controlled by one faction can be a potent weapon against others. That is why the commandos are a conundrum — in the country’s unstable military and political landscape, it is impossible to know where they are heading.

The commandos and their leaders insist that they are loyal to the government rather than to any political or religious group. »There is no Sunni or Shia, » Adnan told me, meaning that he does not pay attention to the religious origins of his men or the insurgents they hunt. »Anyone who tries to stop Iraq from moving forward, I will fight them. » Adnan’s statement is predictable, but is it convincing? The commando chain of command is largely Sunni — they were set up by a Sunni minister (Naqib) and are led by a Sunni general (Adnan). At this point, the commandos consist mainly of two brigades. The commander of one brigade is Rashid al-Halafi, who is Shiite but is regarded warily by other Shiites because he held senior intelligence posts under Saddam Hussein. The other brigade was founded by Gen. Muhammed Muther, a Sunni who commanded a tank regiment under Hussein.

Of course, the commandos are an effective fighting force precisely because of their Sunni background. Sunnis occupied the top positions in Hussein’s security apparatus and are, as a result, the country’s most experienced fighters. They are particularly well suited to fight in the Sunni Triangle — they have deep ties there and can extract more intelligence than outsiders, which is what Shiites and Kurds are considered in Samarra, Baqubah, Falluja, Ramadi and other insurgent strongholds. The Iraqi government improves its ability to fight the insurgents by bringing veteran Sunni military men on board.

Their presence is useful politically, too: it makes it hard for the insurgency to claim that the government ignores Sunni interests. History has shown that the best way to end an insurgency is to bring insurgents or potential insurgents into the political system. The Salvadoran war ended with a 1991 peace accord between the government and the F.M.L.N., the rebel movement, which then grew into a legitimate political party. Similarly, the conflict in Northern Ireland came to an end with the 1998 Good Friday Agreement, which provided for power sharing with Sinn Fein, the political wing of the Irish Republican Army.

The true loyalties of the commandos remain unclear, however. It is difficult to generalize about the reasons ex-Republican Guard generals and soldiers who are Sunni have joined the commandos. Loyalty to the Shiite-dominated government is a possibility. A larger consideration among the rank and file is a good paycheck (by Iraqi standards). Captain Bennett said that their desire to once again earn a living in their old line of work — fighting in a professional military and being paid to do it — is more important than warm feelings for the government.

»For some, there’s definitely a desire to make Iraq better, but for a lot of them, it’s just the life they know, » he said. »For most of them, the cause isn’t really that important. They’re more used to working in this role. This is what they know, this is all they know. I think they feel a lot better that their actions now are against genuine threats, as opposed to threats against the regime, » meaning Hussein’s government. »But I think for a lot of them, they couldn’t fathom doing something different with their lives. »

Whatever the motivations, the integration of the commandos into the security forces stanches one flow of experienced fighters into the insurgency. Some commandos, and perhaps many of them, might have gravitated to the other side if their unemployment endured. »It’s human nature, » said Casteel, the adviser to Naqib, the interior minister. »If you cannot feed your family, you will find a way to feed your family. » Naqib, Casteel explained, sees the commandos »as a way to re-employ people who could be on the other side but have skills that can be used. »

Yet their presence in the new security forces is not universally welcomed. Shiites and Kurds faced mass murder during Hussein’s regime, and they are understandably concerned about giving a share of military power to Sunnis, especially those who served Hussein. They worry that a Sunni-led security force could be a Trojan horse for the return of oppression by Sunnis. Because Naqib chose Hussein-era military figures to lead the commandos, he made few friends among Shiites and Kurds in the interim government, and he is not expected to retain his portfolio in the government being formed by the new prime minister, Ibrahim Jafari, who is Shiite. As Haydar al-Abadi, an influential member of Jafari’s Islamic Dawa Party, told The Wall Street Journal: »The Baathists believe they are back, and that they can behave as before. People are afraid again. »

If Jafari purges former Baathists, the commandos may lose their leaders, including Adnan. That would almost certainly test their loyalties. Secretary of Defense Donald H. Rumsfeld, on a visit to Iraq in April, evoked those concerns, telling reporters, »It’s important that the new government be attentive to the competence of the people in the ministries, and that they avoid unnecessary turbulence. » In the worst case, a purge could prompt some commandos to join the insurgency or evolve into a Sunni militia beyond government control. Already, Iraq has a Kurdish militia, the 90,000-strong pesh merga, outside the control of the central government; there is also the Badr Brigade, the Iranian-trained wing of the Supreme Council for the Islamic Revolution in Iraq, which is Shiite; and there is the Mahdi Army, loyal to the Shiite militant Moktada al-Sadr. The last thing the country needs is another militia.

It is a fraught situation — a country at war without a unified and competent national army. And despite the improved security forces and the reduction in attacks on coalition forces, it is hard to see an end to the war any time soon. Just as the right political developments can tame an insurgency, so too can the wrong developments give new life to it. Arriving at the correct calibration of military force and political compromise is an excruciatingly difficult process. Historically, insurgencies have tended to last for at least 5 to 10 years; the endgame tends to begin when one or both sides become exhausted, and that rarely occurs after only a year or two.

In El Salvador, Honduras, Peru, Turkey, Algeria and other crucibles of insurgency and counterinsurgency, the battles went on and on. They were, without exception, dirty wars.

Peter Maass, a contributing writer, is the author of »Love Thy Neighbor: A Story of War. » He has reported extensively for the magazine from Iraq.

*************************************************************************

Repère:

Deux soldats britanniques déguisés en irakiens avec habits et barbe ,étaient planqués dans une voiture, attendant le moment pour passer à l’action. Quelles actions justement ? Ils étaient lourdement armés avec des explosifs de TNT, des détonateurs, des moyens de communication et d’autres moyens pour faire du « bruit ».

Ces « soldats » ont répliqué quand des policiers irakiens sont venus les controler. En effet , leur manège a été repéré par des irakiens qui ont averti la police. Ils ont finalement été arrêté et emmenés pour enquête au poste. L’armée anglaise mise au courant a exigé immédiatement de les relâcher sur le champ sans donner des explications.

Devant le refus des irakiens d’obtempérer , ils ont mobilisé leur moyens les plus lourds et ont détruit les murs du poste irakien et ont délivré leurs « soldats ». [1]

[1]http://news.bbc.co.uk/hi/arabic/middle_east_news/newsid_4262000/4262372.stm

____________________________________________________

Puis voici quelques articles dans la même perspective:

1. ‘The Salvador Option’ by Michael Hirsh :http://www.thedailybeast.com/newsweek/2005/01/07/the-salvador-option.html

2. « From Iran-contra to Iraq », David Corn on May 6, 2005 :http://www.thenation.com/blog/156167/iran-contra-iraq

4. Escadrons de la mort, l’école française :www.algeria-watch.de/fr/article/div/livres/escadrons_mort_conclusion.htm

Et puis pour terminer voici l’excellent reportage réalisé par Paul Moreira « Irak: agonie d’une nation » , à regarder notamment à partir de la 49ème minute.

Un mot à Retenir: James Steele et les » Escadrons de la mort » !

____________________________________________________

Le documentaire réalisé par Marie-Monique Robin « Les escadrons de la mort – L’école française » :

[youtube:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TOx-pw3bqlw%5D

****************************************************************

06.05.2005 | David Corn | The Nation

The George W. Bush presidency has been one long rehab session for the Iran-contra scoundrels of the Reagan-Bush administration. Many infamous veterans of the foreign policy connivance of the Reagan days have found a home in Bush II. Elliott Abrams–who pleaded guilty to misleading Congress regarding the Reagan administration’s secret support of the contra rebels fighting the Sandinista government of Nicaragua–was hired as a staff member of George W. Bush’s National Security Council and placed in charge of democracy promotion. Retired Admiral John Poindexter–who was Reagan’s national security adviser, who supervised Oliver North during the Iran-contra days, and who was convicted of several Iran-contra crimes before the convictions were overturned on a legal technicality–was retained by the Pentagon to search for terrorists using computerized Big Brother technology. John Negroponte–who as ambassador to Honduras in the early 1980s was the on-the-ground overseer of pro-contra operations there–was recruited by Bush to be UN ambassador, then ambassador to Iraq, and, most recently, the first director of national intelligence. Otto Reich–who mounted an arguably illegal pro-contra propaganda effort when he was a Reagan official–was appointed by Bush to be in charge of Latin American policy at the State Department. Now comes the news that another Iran-contra alum–a fellow who failed a polygraph test during the Iran-contra investigation–is playing a critical role in Bush’s war in terrorism.

James Steele was recently featured in a New York Times Magazine story as a top adviser to Iraq’s « most fearsome counterinsurgency force, » an outfit called the Special Police Commandos that numbers about 5000 troops. The article, by Peter Maass, noted that Steele « honed his tactics leading a Special Forces mission in El Salvador during that country’s brutal civil war in the 1980s. » And, as Maass reminded his readers, that civil war resulted in the deaths of 70,000 people, mostly civilians, and « [m]ost of the killing and torturing was done by the army and right-wing death squads affiliated with it. » The army that did all that killing in El Salvador was supported by the United States and US military officials such as Steele, who was head of the US military assistance group in El Salvador for two years in the mid-1980s. (A 1993 UN truth commission, which examined 22,000 atrocities that occurred during the twelve-year civil war in El Salvador, attributed 85 percent of the abuses to the US-backed El Salvador military and its death-squad allies.)

Maass reported that the Special Forces advisers in El Salvador led by Steele « trained front-line battalions that were accused of significant human rights abuses. » But he neglected to mention that Steele ran afoul of the Iran-contra investigators for not being honest about his role in the covert and illegal contra-support operation.

After the Iran-contra story broke in 1986, Steele was questioned by Iran-contra investigators, who had good reason to seek information from him. The secret contra-supply network managed by Oliver North had flown weapons and supplies to the contras out of Illopongo Air Base in El Salvador. Steele claimed that he had observed the North network in action but that he had never assisted it. The evidence didn’t support this assertion. For one, North had given Steele a special coding device that allowed encrypted communications to be sent securely over telephone lines. Why did Steele need this device if he had nothing to do with the operation? And for a time Steele passed this device to Felix Rodriguez, one of North’s key operatives in El Salvador. Furthermore, Congressional investigators discovered evidence indicating that aviation fuel given to El Salvador under a US military aid program that Steele supervised was illegally sold to the North network. (The Reagan administration refused to respond to congressional inquiries about this oil deal.) And according to the accounts of others, Steele had made sure that the North network’s planes, used to ferry weapons to the contras, could come and go from Illopongo.

*****

Don’t forget about DAVID CORN’s BLOG at http://www.davidcorn.com. Read recent postings on the latest in national security scandals (that haven’t quite become full-blown scandals), Pat Robertson’s bigotry, and how the Bush administration has screwed up both the hunt for bin Laden and planning for a nuclear terrorist attack.

*******

When questioned by the Iran-contra independent counsel, Steele maintained that he had limited his actions to providing humanitarian assistance to the contras–an act that would not have violated the prohibition passed by Congress on supplying the contras with weapons. But, as independent counsel Lawrence Walsh later pointed out in his book, Firewall, a lie-detector examination indicated Steel « was not being truthful. » Steele’s name had also turned up in the private notebooks in which North kept track of his various Iran-contra operations. As Walsh wrote, « Confronted with the results of the lie-detector test and North’s notebook, Steele admitted not only his participation in the [clandestine] arms deliveries [to the contras] but also his early discussions of these activities with Donald Gregg [the national security adviser to Vice President George Bush] and the U.S. ambassador to El Salvador, Edwin G. Corr. »

Walsh’s description suggested that Steele tried to lie his way past investigators as part of a larger cover-up. At the time of the scandal, a significant question was how much Donald Gregg knew about the operation in El Salvador, for Gregg’s connection to the secret, law-skirting contra-support network implicated Vice President Bush, who was running for president and claiming he had been out of the loop on the Iran-contra affair. (George H.W. Bush’s own diaries–which he withheld for several years and did not release until after he had lost his 1992 bid for reelection as president–prove that despite his claim of ignorance he knew about the Iran-contra affair before it became public.) Steele had played the good soldier–that is, he did not tell the truth and kept his mouth shut as long as he could.

Steele escaped indictment and his flunking of the polygraph exam was not revealed until Walsh’s book came out in 1997. But he did have to pay for his participation in the North’s contra scheme. In 1988, the Pentagon sent to the Senate a list of 50 Army colonels who were up for promotion to brigadier general. An a list of proposed promotions to full colonel submitted at the same time included Lt. Colonel Robert Earl, a North deputy who assisted the contra supply effort and participated in the destruction of records after the Iran-contra scandal exploded. Usually such promotions fly though the Senate with no debate. But aides working for Senator Tom Harkin, a Democrat from Iowa, noticed Steele’s and Earl’s names on these lists, and Harkin blocked these two promotions. « There is no way any of these people is going to get a promotion » without a congressional inquiry, Harkin told The Washington Post. The Army claimed that it had found that Steele had committed nothing wrong. Obviously, it had not looked hard enough, for, as Walsh later determined, Steele had not told the truth.

But misleading congressional and independent investigators didn’t fully derail Steele’s career. He is once more advising a military unit with a questionable human rights record. Let’s hope that if his actions this time around become of interest to government investigators he is truthful when they come knocking.

L’excellent reportage à regarder notamment à partir de la 49ème minute.

Un mot à Retenir: James Steele et les » Escadrons de la mort » !

‘The Salvador Option’

07.05.2005 | John Barry & Michael Hirsh | The Daily Beast

What to do about the deepening quagmire of Iraq? The Pentagon’s latest approach is being called « the Salvador option »–and the fact that it is being discussed at all is a measure of just how worried Donald Rumsfeld really is. « What everyone agrees is that we can’t just go on as we are, » one senior military officer told NEWSWEEK. « We have to find a way to take the offensive against the insurgents. Right now, we are playing defense. And we are losing. » Last November’s operation in Fallujah, most analysts agree, succeeded less in breaking « the back » of the insurgency–as Marine Gen. John Sattler optimistically declared at the time–than in spreading it out.

Now, NEWSWEEK has learned, the Pentagon is intensively debating an option that dates back to a still-secret strategy in the Reagan administration’s battle against the leftist guerrilla insurgency in El Salvador in the early 1980s. Then, faced with a losing war against Salvadoran rebels, the U.S. government funded or supported « nationalist » forces that allegedly included so-called death squads directed to hunt down and kill rebel leaders and sympathizers. Eventually the insurgency was quelled, and many U.S. conservatives consider the policy to have been a success–despite the deaths of innocent civilians and the subsequent Iran-Contra arms-for-hostages scandal. (Among the current administration officials who dealt with Central America back then is John Negroponte, who is today the U.S. ambassador to Iraq. Under Reagan, he was ambassador to Honduras. There is no evidence, however, that Negroponte knew anything about the Salvadoran death squads or the Iran-Contra scandal at the time. The Iraq ambassador, in a phone call to NEWSWEEK on Jan. 10, said he was not involved in military strategy in Iraq. He called the insertion of his name into this report « utterly gratuitous. »)

Following that model, one Pentagon proposal would send Special Forces teams to advise, support and possibly train Iraqi squads, most likely hand-picked Kurdish Peshmerga fighters and Shiite militiamen, to target Sunni insurgents and their sympathizers, even across the border into Syria, according to military insiders familiar with the discussions. It remains unclear, however, whether this would be a policy of assassination or so-called « snatch » operations, in which the targets are sent to secret facilities for interrogation. The current thinking is that while U.S. Special Forces would lead operations in, say, Syria, activities inside Iraq itself would be carried out by Iraqi paramilitaries, officials tell NEWSWEEK.

Also being debated is which agency within the U.S. government–the Defense department or CIA–would take responsibility for such an operation. Rumsfeld’s Pentagon has aggressively sought to build up its own intelligence-gathering and clandestine capability with an operation run by Defense Undersecretary Stephen Cambone. But since the Abu Ghraib interrogations scandal, some military officials are ultra-wary of any operations that could run afoul of the ethics codified in the Uniform Code of Military Justice. That, they argue, is the reason why such covert operations have always been run by the CIA and authorized by a special presidential finding. (In « covert » activity, U.S. personnel operate under cover and the U.S. government will not confirm that it instigated or ordered them into action if they are captured or killed.)

Meanwhile, intensive discussions are taking place inside the Senate Intelligence Committee over the Defense department’s efforts to expand the involvement of U.S. Special Forces personnel in intelligence-gathering missions. Historically, Special Forces’ intelligence gathering has been limited to objectives directly related to upcoming military operations–« preparation of the battlefield, » in military lingo. But, according to intelligence and defense officials, some Pentagon civilians for years have sought to expand the use of Special Forces for other intelligence missions.

Pentagon civilians and some Special Forces personnel believe CIA civilian managers have traditionally been too conservative in planning and executing the kind of undercover missions that Special Forces soldiers believe they can effectively conduct. CIA traditionalists are believed to be adamantly opposed to ceding any authority to the Pentagon. Until now, Pentagon proposals for a capability to send soldiers out on intelligence missions without direct CIA approval or participation have been shot down. But counter-terrorist strike squads, even operating covertly, could be deemed to fall within the Defense department’s orbit.

The interim government of Prime Minister Ayad Allawi is said to be among the most forthright proponents of the Salvador option. Maj. Gen.Muhammad Abdallah al-Shahwani, director of Iraq’s National Intelligence Service, may have been laying the groundwork for the idea with a series of interviews during the past ten days. Shahwani told the London-based Arabic daily Al-Sharq al-Awsat that the insurgent leadership–he named three former senior figures in the Saddam regime, including Saddam Hussein’s half-brother–were essentially safe across the border in a Syrian sanctuary. « We are certain that they are in Syria and move easily between Syrian and Iraqi territories, » he said, adding that efforts to extradite them « have not borne fruit so far. »

Escadrons de la mort, l’école française | Livre publié le 2 septembre 2004 | Marie-Monique Robin

L’histoire continue.

Au Parlement français : de la reconnaissance au déni de la réalité

« J’ai été bouleversé par ce documentaire et je dois dire que j’ai honte pour la France. J’espère que nous aurons le courage de faire toute la lumière sur cette face cachée de notre histoire pour que nous ayons enfin le droit de nous revendiquer comme la patrie des droits de l’homme. » C’était le 10 mars 2004 sous les lambris du Palais du Luxembourg. Ancien ministre et actuel médiateur de la République, Bernard Stasi a été désigné par les organisateurs de la neuvième édition des « Lauriers de la radio et de la télévision au Sénat » pour me remettre le prix du « meilleur documentaire politique de l’année ». À dire vrai, quand un mois plus tôt, j’avais été informée du choix du jury, présidé par Marcel Jullian, j’avais d’abord cru à une erreur. Un prix au Sénat pour « Escadrons de la mort : l’école française » : la nouvelle paraissait incroyable ! Ma surprise est à son comble quand j’entends les mots courageux de Bernard Stasi, premier homme politique français – à ma connaissance – à assumer ainsi publiquement la « face cachée de notre histoire ».

Car, il faut bien le reconnaître, après la diffusion de mon documentaire sur Canal Plus, le lundi 1er septembre 2003, la classe politique et la presse françaises ont fait preuve d’une belle unanimité : silence radio, ou, pour reprendre l’expression de Marie Colmant, « apathie générale ». « On guette la presse du lendemain, écrit l’éditorialiste de l’hebdomadaire Télérama, on regarde les infos, en se disant que ça va faire un fameux barouf, que quelques députés un peu plus réveillés que les autres vont demander une enquête parlementaire, que la presse va prendre le relais. Mardi, rien vu, à l’exception d’un billet en bas de page dans la rubrique télé d’un grand quotidien du soir. Mercredi rien vu. Jeudi rien vu. Vendredi, toujours rien vu. Je ne comprends pas. C’est quoi ce monde « mou du genou » dans lequel on vit[1] ? »

C’est vrai qu’il y a de quoi s’offusquer de cette bonne vieille spécificité française : tandis qu’aux États-Unis, la publication de photos, par la chaîne CBS, montrant l’usage de la torture en Irak par des militaires américains déclenchera en avril 2004 une crise légitime outre-Atlantique et fera la une des journaux français pendant une quinzaine de jours, les déclarations, documents à l’appui, d’une palanquée de généraux français, nord et sud-américains et d’un ancien ministre des Armées sur le rôle joué par le « pays des droits de l’homme » dans la genèse des dictatures du Cône sud ne provoquent en France que. l’indifférence générale.

Ou presque : le 10 septembre 2003, le jour où paraît le numéro précité de Télérama, les députés Verts Noël Mamère, Martine Billard et Yves Cochet déposent une demande de commission d’enquête parlementaire sur le « rôle de la France dans le soutien aux régimes militaires d’Amérique latine de 1973 à 1984[2] », auprès de la commission des Affaires étrangères de l’Assemblée nationale, présidée par Édouard Balladur. Pas un journal, à l’exception du Monde[3], ne se fait l’écho de cette demande. Qu’importe : on se dit, à l’instar de Marie Colmant, qu’il existe bien, en France, « quelques députés plus réveillés que les autres » et que quelque chose va, enfin, se passer. Nenni ! Nommé rapporteur, le député Roland Blum, qui, malgré ma demande écrite, n’a même pas daigné m’auditionner, publie, en décembre 2003, son « rapport » : douze pages où la langue de bois rivalise avec la mauvaise foi[4].

On peut notamment y lire : « La proposition de résolution est fondée, sur un point, sur des faits inexacts. En effet, elle émet le souhait qu’une éventuelle commission d’enquête puisse étudier le « rôle du ministère des Armées et en particulier l’application des accords de coopération entre la France, le Chili, le Brésil et l’Argentine entre 1973 et 1984 ». Or, aucun accord de coopération militaire entre la France et l’un de ces trois pays d’Amérique latine n’était applicable lors de la période considérée. [.] Aucun accord de ce type ne figure au recueil des accords et traités publié par le ministère des Affaires étrangères. » Roland Blum – c’est un comble ! – n’a manifestement pas vu mon documentaire, où je montre une copie de l’accord, signé en 1959, entre la France et l’Argentine, pour la création d’une « mission permanente militaire française » à Buenos Aires, laquelle perdurera jusqu’à la fin des années 1970, ainsi que le prouvent les documents que je produis également à l’antenne (voir supra, chapitres 14 et 20). D’ailleurs, si le rapporteur avait fait l’effort de me contacter, j’aurais pu lui indiquer où retrouver ledit accord dans les archives du Quai d’Orsay[5].

Fondé sur le déni pur et simple, le reste du rapport procède du même tonneau négationniste. En voici quelques morceaux choisis : « Que des généraux argentins ou chiliens indiquent qu’ils ont appliqué des méthodes enseignées par d’autres peut se comprendre : ils cherchent à atténuer leur responsabilité individuelle en faisant croire qu’ils agissaient dans le cadre d’une lutte mondiale contre le communisme, mais cela ne doit pas nous faire oublier que les tortionnaires en question ne sont pas vraiment des témoins dignes de confiance. [.] La politique française à l’égard de l’Amérique latine fut à l’époque dépourvue de toute ambiguïté. Au-delà des condamnations verbales de ces régimes, la France agissait concrètement en accueillant massivement des réfugiés de ce pays. [.] Certes, il n’est pas inenvisageable que des personnes de nationalité française aient pu participer à des activités de répression, mais si cela a été le cas, ce fut à titre individuel. »

La lecture du rapport devant la commission des Affaires étrangères a provoqué quelques remarques acerbes du député Noël Mamère, qui a estimé que « les arguments avancés par le rapporteur n’étaient ni valables ni justifiés. Leur seul objectif est d’éviter de faire la lumière et de travestir la vérité ». Venant à la rescousse de son collègue Vert, le député socialiste François Loncle a, quant à lui, « souligné l’intérêt pour les membres de la commission parlementaire de visionner ce documentaire ». Chose que ceux-ci n’ont pas jugé nécessaire, puisque « conformément aux conclusions du rapporteur, la commission a rejeté la proposition de résolution ».

Le déni, encore et toujours. Voilà l’attitude adoptée systématiquement par les gouvernants du « pays des droits de l’homme » chaque fois que des journalistes ou des historiens tentent de lever le voile qui couvre la face peu glorieuse de l’histoire post-coloniale de la France. Le ministre des Affaires étrangères Dominique de Villepin s’est lui aussi comporté en bon petit soldat de l’omerta institutionnelle, lorsqu’il a effectué, en février 2004, une visite officielle au Chili, où les journaux avaient largement rendu compte de mon film[6]. Interrogé à ce sujet lors d’une conférence de presse, le ministre de la République s’est contenté de nier purement et simplement toute forme de collaboration de l’armée ou du gouvernement français avec les dictatures latino-américaines, en laissant entendre que l’enquête sous-tendant le documentaire, qu’il n’a selon toute vraisemblance pas vu, n’était pas sérieuse[7].

La « doctrine française » au cour du génocide rwandais

Après la lecture de l’interview réalisée par ma consour du Mercurio, j’ai eu envie de prendre ma plume pour écrire à Dominique de Villepin. Finalement, je ne l’ai pas fait, mais j’ai lu, depuis, le long essai que lui a adressé Patrick de Saint-Exupéry, journaliste au Figaro, qui lui reproche un autre déni : celui du génocide perpétré au Rwanda par les Hutus contre les Tutsis, d’avril à juin 1994[8]. Un déni, qui, en réalité, en cache un autre : celui du rôle joué par la France dans la genèse du troisième génocide du XXe siècle, où plus de 800 000 innocents furent massacrés en cent jours.

Appelé à témoigner en janvier 2004 devant le tribunal pénal international d’Arusha (Tanzanie), dont la mission est de juger les responsables du génocide rwandais, le général canadien Roméo Dallaire, commandant des forces de l’ONU au Rwanda, expliquera : « Tuer un million de gens et être capable d’en déplacer trois à quatre millions en l’espace de trois mois et demi, sans toute la technologie que l’on a vue dans d’autres pays, c’est tout de même une mission significative. Il fallait qu’il y ait une méthodologie. Cela suppose des données, des ordres ou au moins une coordination[9]. » Celui qui commandait alors les 2 500 casques bleus de la Mission des Nations unies d’assistance au Rwanda (Minuar) et qui, après une longue dépression, a fini par écrire ses mémoires[10], s’est fait plus explicite dans une interview à Libération : « Les Belges et les Français avaient des instructeurs et des conseillers techniques au sein même du quartier général des forces gouvernementales, ainsi que dans les unités d’élite qui sont devenues les unités les plus extrémistes. [.] Des officiers français étaient intégrés au sein de la garde présidentielle, qui, depuis des mois, semait la zizanie et empêchait que les modérés puissent former un gouvernement de réconciliation nationale[11]. »

Qui étaient ces Français et quelle était leur mission ? C’est précisément le cour de l’enquête de Patrick de Saint-Exupéry, qui rappelle qu’en 1990, le président François Mitterrand décida de s’engager résolument aux côtés de son homologue Juvénal Habyarimana, arrivé au pouvoir au Rwanda après un coup d’État sanglant. Représentant la majorité hutue du pays, le dictateur se dit alors menacé par les rebelles tutsis du Front patriotique rwandais de Paul Kagamé, soutenus par l’Ouganda anglophone. Et c’est là que resurgirent les vieux démons coloniaux de la « patrie des droits de l’homme » : obsédé par le « complexe de Fachoda[12] », le président Mitterrand craignait de voir tomber le Rwanda dans le giron anglo-saxon, en l’occurrence américain. Or, le « pays des mille collines », c’est bien connu, fait partie du pré-carré français.

Dans l’entourage présidentiel, on susurre que les États-Unis ont décidé de parrainer une « guerre révolutionnaire » contre la France, menée par le FPR, dont le chef Paul Kagamé, rappelle-t-on opportunément, a été formé à Cuba et à. Fort Bragg. C’est ainsi que, le 4 octobre 1990, après une « manipulation[13] » simulant une fausse attaque des « rebelles » à Kigali, Paris vole au secours de Habyarimana en envoyant des « renforts ». « De 1990 à 1993, nous avons eu cent cinquante hommes au Rwanda, dont le boulot était de former des officiers et sous-officiers rwandais, écrit Patrick de Saint-Exupéry. Ces hommes étaient issus du 8e régiment parachutiste d’infanterie de marine (RPIMa) et du 2e REP, deux régiments de la 11e division parachutiste (DP), le creuset du service Action, le bras armé de la DGSE[14]. » La DGSE, qui, on l’a vu, s’appelait SDECE du temps où un certain général Aussaresses officiait précisément au service Action.

Un extrait du rapport établi par la mission d’enquête parlementaire qui, à la fin de 1998, essaya de faire la lumière sur le rôle de la France au Rwanda, donne une idée précise du « boulot » effectué par les « renforts » français : « Dans le rapport qu’il établit le 30 avril 1991, au terme de sa deuxième mission de conseil, le colonel Gilbert Canovas rappelle les aménagements intervenus dans l’armée rwandaise depuis le 1er octobre 1990, notamment :

– la mise en place de secteurs opérationnels afin de faire face à l’adversaire ; [.]

– le recrutement en grand nombre de militaires de rang et la mobilisation des réservistes, qui a permis un quasi-doublement des effectifs ; [.]

– la réduction du temps de formation initiale des soldats, limitée à l’utilisation de l’arme individuelle en dotation ; [.]

– une offensive médiatique menée par les Rwandais[15]. »

Et Patrick de Saint-Exupéry de décoder le langage militaire, en appliquant le jargon caractéristique de la « doctrine française » : « Ces mots nous décrivent un type précis de guerre, écrit-il :

« Secteurs opérationnels », cela signifie « quadrillage ».

« Recrutement en grand nombre », cela signifie « mobilisation populaire ».

« Réduction du temps de formation », cela signifie « milices ».

« Offensive médiatique », cela signifie « guerre psychologique »[16]. »

De fait, ainsi qu’il ressort des documents d’archives consultés par mon confrère du Figaro, « la France prend les rênes de l’armée rwandaise », deux ans avant le génocide. Le 3 février 1992, une note du Quai d’Orsay à l’ambassade de France à Kigali met celle-ci devant le fait accompli : « À compter du 1er janvier 1992, le lieutenant-colonel Chollet, chef du détachement d’assistance militaire et d’instruction (DAMI), exercera simultanément les fonctions de conseiller du président de la République, chef suprême des Forces armées rwandaises (FAR), et les fonctions de conseiller du chef d’état-major de l’armée rwandaise. » La note précise que les pouvoirs de l’officier français auprès du chef d’état-major consistent à « le conseiller sur l’organisation de l’armée rwandaise, l’instruction et l’entraînement des unités, l’emploi des forces[17] ».

Tandis que les instructeurs français du DAMI forment dans les camps militaires rwandais des unités, qui seront, plus tard, le fer de lance du génocide, Paris reste sourd aux dénonciations de massacres qui émaillent le début des années 1990, et continue d’armer massivement le Rwanda[18]. « Nous n’avons tenu ni machettes, ni fusils, ni massues. Nous ne sommes pas des assassins, commente, meurtri, Patrick de Saint-Exupéry. Nous avons instruit les tueurs. Nous leur avons fourni la technologie : notre « théorie ». Nous leur avons fourni la méthodologie : notre « doctrine ». Nous avons appliqué au Rwanda un vieux concept tiré de notre histoire d’empire. De nos guerres coloniales. Des guerres qui devinrent « révolutionnaires » à l’épreuve de l’Indochine. Puis se firent « psychologiques » en Algérie. Des « guerres totales ». Avec des dégâts totaux. Les « guerres sales »[19]. » Et d’ajouter : « Cette doctrine fut le ressort du piège [.] qui permit de transformer une intention de génocide en génocide. [.] Sans lui, sans ce ressort que nous avons fourni, il y aurait eu massacres, pas génocide[20]. »

À ceux qui voudraient se raccrocher aux branches de la bonne conscience en se disant qu’après tout le « pays des droits de l’homme » ne pouvait pas prévoir quelle serait l’ampleur du drame en gestation, le journaliste du Figaro apporte de nouveaux éléments qui terrasse leurs dernières illusions : du 17 au 27 septembre 1991, Paul Kagamé, le chef des « rebelles » tutsis a effectué une « visite en France au cours de laquelle il a pu rencontrer MM. Jean-Christophe Mitterrand et Paul Dijoud », note un télégramme diplomatique, cité dans le rapport de la mission d’enquête parlementaire[21]. C’est lors d’un rendez-vous avec Paul Dijoud, le directeur des Affaires africaines au Quai d’Orsay, que le futur président rwandais aurait entendu celui-ci proférer de sombres menaces : « Si vous n’arrêtez pas le combat, si vous vous emparez du pays, vous ne retrouverez pas vos frères et vos familles, parce que tous auront été massacrés[22] », aurait dit celui qui occupera plus tard le poste d’ambassadeur de France en Argentine, au moment où j’enquête pour mon film Escadrons de la mort : l’école française.

En lisant ces lignes, j’ai frémi : la veille de mon départ pour Buenos Aires, j’avais failli informer l’ambassade de France de mes projets, estimant que mon tournage comportait quelques risques et qu’il convenait peut-être d’aviser le représentant des autorités françaises. « Je te le déconseille, m’avait dit Horacio Verbitsky. Dijoud est comme cul et chemise avec les militaires argentins, et il vaut mieux que tu restes le plus discrète possible, si tu ne veux pas faire capoter tes interviews avec les anciens généraux de la junte. »

En attendant, une chose est sûre : fin avril 1994, alors que le génocide rwandais bat son plein, une délégation du « gouvernement intérimaire » de Kigali est reçue à l’Élysée, à Matignon et au Quai d’Orsay. Parmi les dignitaires criminels en visite à Paris, il y a notamment Jean-Bosco Barayagwiza, le chef politique des extrémistes hutus et actionnaire de Radio Mille Collines, qui sera condamné en décembre 2003 par le Tribunal pénal international d’Arusha à trente-cinq ans de prison.

Les guerres sales d’Irlande, de Bosnie et de Tchétchénie